“I can hear with my knee better than with my calves.” This statement made by Bernhard Leitner, which initially seems absurd, can be explained in light of an interest that he still pursues today with unbroken passion and meticulousness: the study of the relationship between sound, space, and body. Since the late 1960s, Bernhard Leitner has been working in the realm between architecture, sculpture, and music, conceiving of sounds as constructive material, as architectural elements that allow a space to emerge. Sounds move with various speeds through a space, they rise and fall, resonate back and forth, and bridge dynamic, constantly changing spatial bodies within the static limits of the architectural framework. Idiosyncratic spaces emerge that cannot be fixed visually and are impossible to survey from the outside, audible spaces that can be felt with the entire body. Leitner speaks of “corporeal” hearing, whereby acoustic perception not only takes place by way of the ears, but through the entire body, and each part of the body can hear differently.

- George Kargl, Fine Arts Vienna

Bernhard Leitner is considered a pioneer of the art form generally referred to as “sound installation.” He introduced sound to the installation space, allowing the installation space to emerge through the sound. Leitner, who actually studied architecture, has been a visionary ever since the very start of his artistic career. His sculptures—which he refers to as “sound-space objects”—and installations are the result of long, complex processes of development. In precise sketches and workbooks, he first approaches the sculptural, architectural qualities of sound in theory.

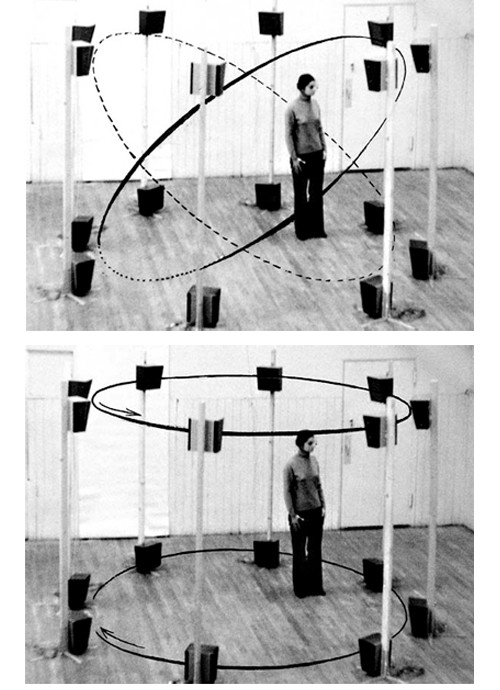

He undertakes, as it were, foundational scientific research by studying frequencies, volumes, movements and combinations of sounds and their impact on the body, sketching possible spatial figures, such as cubes, corridors, fields, pipes, and exploring the impact of bodily posture on acoustic perception. In 1968 Leitner moved to New York, where he concretely began working on sound-space studies in his studio. He developed multi-channel compositions using sound recordings that were not musically conceived, from which he extracted specific sound material and combined it in work-specific series of sounds. He then notated these series using visual codes that he himself developed consisting of letter combinations on rolls of paper, and transferred them to perforated tape.

This resulted in temporary installations of wooden slats on which loudspeakers could be arranged in various geometric arrangements. These were operated individually by way of a control device developed together with a technician, for this was not possible with devices found on the market with the then current state of technology. In this way, Leitner was able for the first time to place sounds and series of sounds in various, exactly performed movements that create “spatial models in an invisible (new) geometry.”

The visual formulation of Leitner’s installations can be read in the tradition of the aesthetics of New York minimalism in the 1970s. There are echoes of Richard Serra, Carl Andre, or Donald Judd, even if the reduced and strict formal language of Bernhard Leitner enters into a new functional context that “serves to shift attention from the visual to the acoustic level of the installation.” In the moment when the visitor is no longer unnecessarily distracted by visual stimuli, acoustic attentiveness automatically increases.

At a first glance, the simplest way of characterizing the sound installation as art form would be to describe it as a combination of art exhibition and concert. In reality, however, the sound installation distinctly sets itself apart from both these closely affiliated art forms and begins to disclose itself more and more as an art form capable of overcoming those deficits which one distinctly senses in the case of the conventional exhibition as well as in the conventional concert. Among the most outstanding examples of sound installations are those witnessed in the works of Bernhard Leitner.

In an entirely impressive manner, the artist has been pursuing his own unique course by consistently and convincingly experimenting with the sound installation as an art form. Before embarking on a characterization of the particular complex of problems surrounding Leitner’s works with any degree of precision, one must first clarify a number of misunderstandings which would hinder the elaboration of an adequate understanding of the installation as art form.

As a matter of fact, the difference between the installation and other art forms is easy enough to formulate: In the case of the installation the viewer becomes visitor. The installation is a spatial fragment, a spatial volume, which is to be read as a unified object. The central characteristic of this spatial fragment is that it is a space understood as being empty, abstract and purely geometric. And yet, it is precisely this chief characteristic of the installation that poses such a challenge to perception and interpretation.

Since the space of installation represents an empty space, it can be all too easily overlooked. As any other space, the space of installation may therefore be filled with diverse objects; it can be entered and offers the possibility to move around freely within it. In this sense, the space of installation would appear as being “immaterial”, indeed,non-existent and thus incapable of assuming the role of a medium of art. It is for this reason that our attention is almost involuntarily drawn away from the empty space itself and rather towards the objects within it. As a consequence, the installation is misunderstood as a specific arrangement of objects within space – and not as the space itself.

Thus, the use of sound within the installation space is in no way external to it. Quite to the contrary: the wonder of sound consists in the fact that it fills space. For this reason, sound can best serve as an indicator of holistic space insofar as it is capable of inducing in the viewer the sense of becoming part of the entire space. And it is in just such a way that Leitner’s sound installations function. Here, a single sound does not necessarily fill the entire exhibition space. It is far more that each of these single sounds creates its own space in which the viewer/visitor must enter.

In the process, the visitor inevitably becomes aware of his own body as being part of the unified space of the sound installation. Firstly, a specific spatial position or even pose is designated for his body. And secondly, within the sound installation the visitor is given the feeling that the tone, which fills the installation space, also flows through his own body. The limits of his own body are consequenty put into question and relativized – and he begins to perceive himself as part of the space of the installation as a whole.

The experience of being physically permeated by sound when listening to sound in one of Leitner’s installations differs decisively from the experience of listening to music in a concert hall, for example. In the concert hall, the music also fills the entire room and yet this space is visually divided in two. In the hall, the listener is territorialized, the music produced on stage. In this case, the usual exhibition or theatrical staging situation is repeated: the listening audience becomes the spectator who finds himself in the position of being in front of the artwork.

It is in this way that the listener in the concert hall has the sense of “being seated in front of the music” – even though the music can be heard everywhere within the space. This feeling makes it impossible for the listener to comprehend his own body as being part of the music space, of the sound space. Furthermore, added to this is the temporal limitation of the concert. As a rule, the time frame of the concert is designed with the visitor in mind – the end of the concert is also the end of the music.

If one has endured the concert from beginning to end, one knows that one has consumed everything that was possible and necessary to consume. By contrast, the final satisfaction, that familiar feeling of having well and truly heard and seen everything is denied the visitor of Leitner’s installations: here, the sound has already begun before the visitor has taken his seat – and continues even after he has left this seat. The presence or absence of the visitor makes no particular impression on the sound itself – it continues beyond the span of his attention. Hence, the viewer leaves the exhibition with the sense of having only briefly been in the sovereign position of hearing, though not of having taken possession of it.

It is necessary to rethink and redefine the term “space”. The boundaries of these spaces cannot be experienced at once, and they are not “dynamic, fluid” spaces in the conventional interpretation. It is space which has a beginning and an end. Space is here a sequence of spatial sensations – in its very essence an event of time. Space unfolds in time; it is developed, repeated and transformed in time.

Bernhard Leitners’ works deal with the audio-physical experience of spaces and objects which are determined in form and content by movements of sound. The focus is the relationship between built structures of sound and the human body. The scale ranges from small objects directly applied to the body to large-scale architectural spaces.

References: Bernhard Leitner .P.U.L.S.E., Bernhard Leitner Sound : Space, http://www.bernhardleitner.at/en, Boris Groys, George Kargl Photography: Atelier Leitner, Bernhard Leitner