This article was originally published on Common Edge.

Paul Goldberger has a new book out, released just this week, entitled Ballpark: Baseball in the American City. Taking a page from the Ken Burns playbook, the book looks at a particularly American building type as a lens for looking at the broader culture of cities. Goldberger’s premise is a good one: Ballparks do parallel, to a remarkable degree, trends in American urbanism. They start as an escape from the city, then the city builds up around them. Post–World War II, they escape to the suburbs, then decades later return to the city. Today, privatization of the public realm and real estate development are driving the agenda. Recently I talked with Goldberger about the new book and a whole slew of magical ballparks, both living and long gone.

Martin C. Pedersen: Let’s start with two questions: Why does a Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic write a book about baseball stadiums? And for those not interested in baseball, why do ballparks matter?

Paul Goldberger: We could talk for half an hour on the second question. But I’ve always found there’s something magical about a baseball park, about the way it’s both city and country woven together in the most miraculous way. I remember as a kid, the first time I went to Yankee Stadium, being blown away by the most beautiful lawn I’d ever seen in my life, and I grew up in the suburbs, where there were lots of lawns. But I’d never seen one like this, and it was right in the middle of the Bronx. That juxtaposition was powerful for me.

In 2009, when I was at the New Yorker, David Remnick asked me to write about Yankee Stadium and Citi Field, both of which opened that year. As I researched the piece, I realized how the history of baseball parks is also the history of American cities. It’s a mirror to how we’ve viewed our cities and what we think about them. Baseball parks are a significant part of the public realm; they’re a public experience, in an age when so much is pushed toward private and virtual experience.

MCP: Early in the book, you write about the golden era of baseball stadiums. Talk about some of those ballparks.

PG: The early years of the 20th century are when the idea of the ballpark as a civic building emerges. The ones I highlight are Crosley Field, in Cincinnati; Tiger Stadium, in Detroit—a terrible loss; Wrigley Field, in Chicago; Fenway Park, in Boston; and Ebbets Field, in Brooklyn, which was probably the most tragic loss of all.

MCP: So much mythology grew up around Ebbets Field because so many authors have written about it. Toward the end, though, it was a failing ballpark. What makes it one of the greatest baseball stadiums ever?

PG: The mythology is deeply intertwined with the history of the team, which was incredibly colorful, and an amazing group of fans. So the stadium had a sort of astonishing personality. It was intimate but had a certain aspiration to grandeur at the same time. It emerged out of a time when baseball was a commanding presence in Brooklyn. Baseball was almost an indigenous local sport, with a lot of teams, and a lot of smaller ballparks—Washington Park, and many others—all culminating in the great cathedral of Ebbets Field, which opened in 1913. But it’s also true that by the 1950s, Ebbets had become incredibly rundown. It was always cramped and awkward. It emerged out of a time when we built wonderful public places that, paradoxically, never had enough public space in them. It’s not unlike the way the old Broadway theaters are today.

On the other hand, Ebbets Field had an energy that came from a certain degree of compression. It’s the same way that if you have a dining room table that seats eight people and you squeeze in 10, and they all like each other, they’ll have a better time. Ebbets had that quality and just enough monumentality to give it some architectural airs, but not enough to ever get in the way of the game. Like all great public places, it had a kind of harmonic balance to it. But there’s no question a lot of the myth comes from the people in it—most of all, of course, the team on the playing field.

MCP: Then you had the emergence of Jackie Robinson, which transcended baseball.

PG: Ebbets becomes important as a place in the history of civil rights, a fact that by itself, even if you didn’t care about the architecture, should have been justification for saving it. Today we would never let that happen, but Ebbets was torn down at a time when preservation consciousness was minimal if it existed at all.

The other thing that was interesting to research was the whole story of how the Dodgers ended up leaving Brooklyn. It was not that Walter O’Malley hated Brooklyn and wanted to go to Los Angeles. It was that he hated Ebbets Field and thought it was decrepit, unfixable, unimprovable, and unreachable for a lot of his fans, who were increasingly in the suburbs. So he had this whole scheme with Norman Bel Geddes, of all people. That’s the amazing piece of design history that that has been forgotten. O’Malley hired him to do this huge thing in downtown Brooklyn.

MCP: Which is where the Barclay’s Center stands today.

PG: It’s right there at that intersection. The Bel Geddes scheme is fascinating, but it would have been a disaster. We’re lucky it didn’t happen. There’s no question that putting a proto-Astrodome in downtown Brooklyn would have been a terrible idea. But it was only when that fell apart that O’Malley made the deal with L.A.

MCP: Ironically, Dodger Stadium in L.A. becomes one of few postwar success stories.

PG: Yes. It emerges 100% out of automobile culture, and today we are much more skeptical of that. But if you accept the premise, and you get over the horribleness of getting there and getting out of it, it’s one of the best places anywhere to watch a baseball game. And it’s been made even better with the very respectful and good renovations they’ve done in the last few years.

MCP: What about two survivors from the golden age, Wrigley and Fenway? How did they survive?

PG: Fenway almost didn’t. Prior ownership of the Red Sox was deeply involved in looking at the potential for a new stadium and had gone some distance down the road toward planning a new ballpark. Then new ownership took over, happily willing to make a commitment to stay in Fenway. If the plans to leave Fenway had gone forward, it would have been a huge fight. By that time, many years after the Dodgers left Ebbets Field, there were a lot of people who loved Fenway and understood how good it was. Ownership knew that their fan base would have been very divided about a change.

New ownership brought in Larry Lucchino, the executive who ran the Baltimore Orioles when Camden Yards was built. He’s a deep believer in smaller urban stadiums. Lucchino hired Janet Marie Smith, the architect who worked with him on Camden Yards, and they took the position that you could update Fenway and allow more income to be derived from it without changing its fundamental character. They could add luxury boxes, seats—the seats on top of the Green Monster, most famously.

MCP: That was a brilliant move.

PG: Those seats are the most popular seats in the whole ballpark. They in no way compromise the stadium. Overall, the Fenway redo was an absolutely exquisite job.

The story with Wrigley is different. There was relatively little done to it for a long time, except for putting in lights in 1988, which was considered radical. But when the Ricketts family bought it from the Tribune Company, things began to change. At that point, they realized that the culture of the city was so deeply enmeshed in Wrigley that they couldn’t look into another ballpark. And in fact, I don’t believe there was ever any serious discussion, as there was at Fenway, with replacing it. But they did start to change and update it more aggressively than was done in Boston.

MCP: I think what they did inside the ballpark is quite good. But what they did around the ballpark is sterile.

PG: I would say the same thing. And that’s why, toward the end of the book, I tied that effort to the story of Atlanta. It’s not exactly the same, because Wrigleyville is still a real neighborhood, whereas what Atlanta has done is build entire make-believe, theme-park city out in the suburbs. But in different ways, both the Cubs and the Braves have sought to control outside the ballpark and create a clean, sanitized neighborhood that will make money for them.

MCP: You mentioned Larry Lucchino. He’s a sort of hero in the book because almost everything he touches is good.

PG: In addition to Camden Yards and Fenway he was also involved in San Diego. Petco Park is wonderful.

MCP: It’s one of the few high modern ballparks that works functionally and urbanistically.

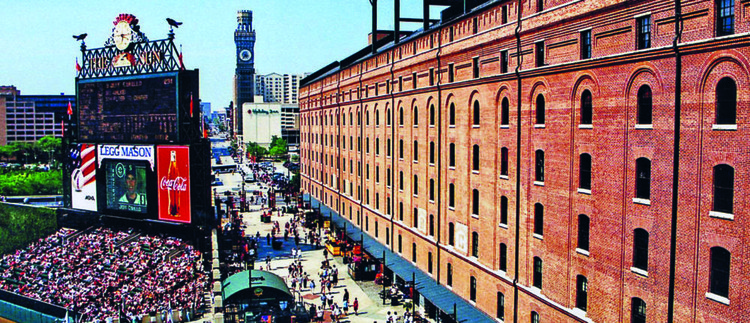

PG: It’s one of the handful of newer generation stadiums that are among the best. The very best is PNC Park, in Pittsburgh. Oracle Park, in San Francisco, and Petco are close seconds. Of course, Camden Yards is historically in a class by itself, because it started the whole thing. It really is a seminal building. I can’t think of any other building type that has been so transformed by one single example. Hospitals, airports—they all continue to evolve, but there’s not one project that changed everything else, 180 degrees, after it. But in baseball, nobody could get away with building a concrete donut anymore after Camden Yards.

MCP: It was interesting that the firm that designed Camden Yards [HOK, whose sports design division later spun off as Populous] also created most of those horrific concrete donuts. I’ve always heard architects say: “You can’t have a good project without a good client.” That seems especially true for baseball stadiums.

PG: Absolutely right. That’s why I spent a lot of time in the chapter on Camden Yards talking about the clients. It was three people: Lucchino, Janet Marie Smith, the team’s in-house architect, and Eli Jacobs. Edward Bennett Williams, the Orioles owner, died shortly after planning for the ballpark had begun, and the team was bought by Jacobs, a rather private financier and investor who went to Yale, studied with Vincent Scully, and became one of those people who, although his professional life had nothing to do with architecture, was obsessed with it. And he drove it more than anybody.

If Jacobs had said, “I don’t care, just build me something to make money,” it would not have turned out the way it did. Jacobs says he was the one who rejected outright the initial HOK design that looked more like a concrete donut. He recalls Lucchino as being unhappy with the first design but hopeful that an improvement could be easily negotiated, whereas Jacobs thought it was necessary to send a stronger message of disapproval, and says he told HOK, “This design is 100% unacceptable.” So there’s a slight difference about the history, but I think this falls into the category of “success has many parents, failure is an orphan.” They all love to take credit for it. But the reality is that they were all pushing in the same direction.

MCP: The New York stadiums are now a decade old. How do they rate?

PG: They’re much better than what they replaced. When the new Yankee Stadium was built, the old Yankee Stadium had been gone for more than 30 years. The renovation of it in the ’70s was so brutal; there was nothing left. If it had been more intact, I might have argued for keeping the old Yankee Stadium. The new one is a nicer place to watch a game. I find it self-consciously grandiose, but it’s still better than what it replaced.

Citi Field is vastly more likable. I would much rather go to a game there. My issue with Citi Field is not the architecture, so much as where it is. To me, it’s an urban ballpark in search of an urban setting. And we missed such a wonderful opportunity: If we’d only put Citi Field on the Hudson Yards site.

MCP: I would vastly prefer Citi Field over the Vessel or the Shed.

PG: A stadium would have taken up more space, but there still would’ve been enough room to build plenty of luxury buildings around it, and it would have meant you could do in New York what people do in Baltimore, Cleveland, Washington, and so many other cities now, which is leave work at 7:00 on a summer day and walk to a baseball game.

MCP: In the last chapter, you write about what the St. Louis Cardinals are doing and what the Atlanta Braves did, creating their own private enclaves. When I read about those developments, I thought: These are just smaller versions of Hudson Yards, with baseball stadiums added.

PG: If Hudson Yards had only had a baseball stadium, it would have been much better. The projects in St. Louis and Atlanta are about the privatization of the public realm. They pretend to urbanism, and the people who build them will even quote Jane Jacobs to you, but it’s all a bit fake and disingenuous, corporate and generic. And that’s where baseball is headed. But once again, it does reflect where the American city is headed. Is it better than the suburban concrete donuts surrounded by 50 acres of parking? Yes. But is it a true vibrant city? No. And Atlanta is especially troubling because—unlike St. Louis or Chicago, which are connected to the real city—SunTrust Park is a theme park built out on the freeway in Cobb County, miles from the city.

MCP: And they had a downtown location that they could have built on.

PG: They claim the city would not allow them to acquire or develop sites around the ballpark. To be fair, their downtown ballpark was not in a great location. Paradoxically, there is more urbanism, of a theme-park variety, in their fake city, than in the real downtown. But there’s another troubling aspect, which is that the new Braves ballpark has the effect, if not the intent, of racism. Cobb is the only county in the Atlanta metro area that’s not part of the Metropolitan Transit System. You can’t really get there unless you have a car. And so a poor African-American kid downtown can’t get to a baseball game very easily, if at all.

MCP: Speaking of race, the demolition of Tiger Stadium was an interesting saga.

PG: A unique saga, and also a sad one. Comerica Park is OK, and it’s right in the center of downtown, which is a good thing. But Tiger Stadium was closer to the central business district than any of the other first-generation stadiums. It could have been saved. By the time the Tigers left, you could not claim—as one could about the Dodgers in Brooklyn—that there was not enough preservation consciousness in the culture. This was 2000. We knew better.

MCP: And there was a Save Tiger Stadium movement.

PG: Huge. But one of the interesting things here is how much of this comes back again to race. I’m convinced that the reason that movement didn’t succeed was that the Detroit government did not support it. It was controlled largely by the African-American community, which had mixed feelings about Tiger Stadium, because Walter Briggs Sr. was one of the more racist owners. For a long time, black people in Detroit thought of Tiger Stadium as a place where they were not particularly welcome. They saw the preservation movement as driven largely by a white suburban fan base. Ultimately, I think if the city government had said this is our No. 1 priority, we’re going to save this stadium, then it would have happened. But in the end, they really didn’t care enough, because it symbolized something to them that was not positive. And the preservationists were not good enough at figuring out how to counter that sad historical fact, if there even was a way to counter it. The Tiger Stadium saga is a reminder that every one of these stadiums has its own story, with its own narrative arc that’s a little bit different, from city to city.