This article was originally published on Metropolis Magazine as "Design Provocateur: Revisiting the Prescient Ideas of Victor Papanek".

“Today industrial design has put murder on a mass-production basis,” declared Victor Papanek, design provocateur and critic, from the podium of a design-activist happening in 1968. “By designing criminally unsafe automobiles that kill or maim,” he roared, “by creating a whole new species of permanent garbage to clutter up the landscape, and by choosing materials and processes that pollute the air we breathe, designers have become a dangerous breed.”

Papanek’s timely polemic—that design was a political tool to be wrested away from corporations and handed back to the public—was concretized in his best-selling 1971 book Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change, which resembled Rachel Carson’s environmentally apocalyptic Silent Spring and Stewart Brand’s counterculture bible Whole Earth Catalog in its tone and urgency. Translated into more than 20 languages, it was a clarion call to a new generation of designers, particularly students, who, armed with Papanek’s searing critique, demanded new socially relevant curricula and an end to straitjacketed formalist design dicta.

The book brims with ideas that still strike a chord nearly a half century on, and its author’s acerbic prose is most welcome at a time when social inclusivity and accountability have become the standard fare of design conglomerates. Papanek, whose work and ideas are the focus of an exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum, curated by Amelie Klein and myself, vigorously took designers to task for elitism and social exclusion, and he promoted community co-design and pro bono schemes that cast users as the crucial participants throughout the design process.

A Viennese émigré who escaped Nazi persecution, Papanek settled in New York just in time for the opening of the 1939 World’s Fair, which exposed him to a seductive vision of a consumer democracy choreographed by celebrity industrial designers such as Raymond Loewy and Norman Bel Geddes. Yet after enrolling in classes at the progressive Cooper Union School of Art, Papanek established his own studio, the Design Clinic, pitting himself against corporate designers whom he accused of failing to address the needs of those who most “suffer design neglect” such as “the rural poor, and the black and white citizens of our inner cities.” Alluding to Loewy, he called on the “new apostles of industrial design” to quit “knocking on the door of the corporations” and to begin “knocking on the doors of developing countries, clinics, hospitals.”

By the early 1960s, Papanek’s rising profile as a critic of mainstream U.S. design placed him in the company of heavyweight thinkers like the maverick inventor and architect Buckminster Fuller and Canadian media theorist and public intellectual Marshall McLuhan. Fuller, who became a lifelong ally, provided the ultimate endorsement by penning the foreword for Papanek’s groundbreaking Design for the Real World. McLuhan, meanwhile, featured the designer’s early critical writing in his cutting-edge coedited journal Explorations. Further inspired by McLuhan’s ideas regarding the societal power of communication technologies, Papanek became one of the first designers to harness the popularity of television as a medium for design criticism. Design Dimensions, a television show aimed at educating the masses on the hazards of bad design, aired in the early 1960s. Papanek wrote and hosted the series, with characteristically polemical and provocative episode titles: “Our Kleenex Culture,” “Do-It-Yourself Murder,” “The Chrome-Plated Marshmallow.”

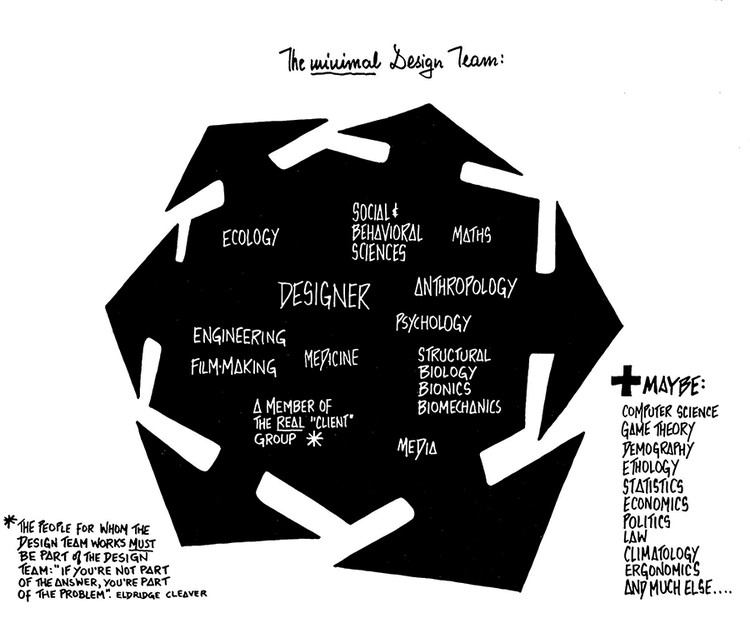

The politics of design Papanek helped delineate reached its apex in 1968, when students and activists ransacked the Milan Triennale in protest against design’s role in bolstering consumer capitalism. The Big Character diagrammatic illustration (available as a pullout poster with the first edition of Design for the Real World) that he co-created with design students at a workshop in Denmark provided a literal blueprint for rebellion, sketching out the dynamics of power at stake for the designer. At its center lay Papanek’s model of the “minimal Design Team,” which championed inclusion and social responsibility through interdisciplinarity, foreshadowing the present-day shift to design anthropology and similar multidisciplinary approaches.

Indeed, in the late 1960s, socially inclusive design presented itself as a radical social instrument that segued into a new design culture of cybernetics, systems thinking, mass communication technologies, and alternative counter-cultures. One of Papanek’s iconic designs from this period, the Tin Can Radio—a DIY-assembly, dung-powered audio player made for distribution in rural Indonesian communities—epitomized this sea change in design thinking. But even in the early 1970s, some critics, among them Ulm School of Design alumnus Gui Bonsiepe, saw these designs as a thinly disguised form of neocolonialism. In a full-blown critique published in Casabella, Bonsiepe accused Papanek outright of collusion with the U.S. military, which, he argued, would appropriate the device as a cheap means of disseminating pro-American propaganda throughout largely non-literate countries. (Papanek, like Fuller, had in fact received limited financial support from the U.S. Army.)

After the success of his first book, and a stint as dean of design at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), Papanek went on to co-author, with design engineer James Hennessey, a number of lesser-known works highlighting the discontents of contemporary product culture: Nomadic Furniture 1 and 2 (1973/1974), and How Things Don’t Work (1977). In 1983, Design for Human Scale merely extended Papanek’s already overplayed polemic and barely registered in a design scene enthralled by the rise of celebrity names. One British design journalist, Stephen Bayley, best known for his enthusiastic promotion of yuppie good taste, dismissed Papanek as “a cult figure while ecology was fashionable during the early seventies.” And so it was that by the 1980s, the idealistic vision of a socially equitable design universe once advocated by design activists lay trampled underfoot by Philippe Starck wannabes.

The Green Imperative (1995) proved to be Papanek’s last foray into the politics of design. It began life as an unpublished, incomplete manuscript titled “The Edifice Complex: Thoughts on Architecture and Design in an Age of Greed,” a direct reference to a term coined to describe former Philippine first lady Imelda Marcos’s predilection for appropriating public funds to finance architectural showpiece projects (and her shoe collection). “The Edifice Complex” was transmuted into The Green Imperative: Ecology and Ethics in Design and Architecture after its publisher recognized the resonance of Papanek’s ideas with those of newly reinvigorated ecological and green politics. Ambitious in its scope, the book was originally planned to have environmentalist James Lovelock (famed theorist of the now-disputed Gaia hypothesis of terrestrial self-regulation) provide the foreword, but he declined. Whereas Design for the Real World had benefited immeasurably from Fuller’s impressive introduction, The Green Imperative remained without an expert endorsement.

Although the book retained the anticonsumerist vitriol of Papanek’s earlier work, its major premise centered on scaling back design to a spiritualized, joyful process that would nurture intuitive connections to the environment, communities, and their values, rather than stoking unbridled consumption. But his well-worn musings on the harmonious design of authentic cultures, coupled with warnings of the detrimental effects of mass marketing, struck a discordant note in an era in which aggressive free-market culture was a stark reality.

Some critics, like U.S. designer Ken Isaacs (an activist and early pioneer of self-build environments), could barely conceal their contempt for the hippie-hangover idealism. “Does one arrive at the spiritual life by meditating in the check-out lane with a Swatch (while wishing for a Rolex)?” he scoffed, before concluding that the ineffectual naïveté of Papanek’s approach was tantamount to “whistling in the cemetery.” Despite its eminently marketable title, The Green Imperative’s optimistic treatise on design’s capacity to effect social transformation proved as anachronistic as its critics had predicted. The indelibly blurred distinctions between Western and indigenous cultures that defined the über-globalized worldview of the mid-1990s made Papanek’s borrowing of native authenticity look suspiciously like old-school cultural appropriation.

And yet certain aspects of the social-design guru’s last testament remain pertinent: the exploration of bionics, the role designers play in accelerating global climate change, and the pressing question of what form design’s socio-environmental accountability might take. Moreover, design remains, as Papanek asserted in the heyday of radical politics, a force as likely to inflict harm as to remedy it. Tasked with shaping our material and immaterial existence, should designers be held answerable to broader humanitarian goals, or merely to the whims of their techno-ideological paymasters? Just how far does their responsibility extend to the aftereffects of their work, be it a driverless vehicle or a disposable diaper? Although the global efficacy of much of today’s social design is debatable, Papanek’s clarion call to action and the feverish polemicizing of Design for the Real World are still relevant.

.jpg?1549283376)