This article was originally published by The Architect's Newspaper in their April 2017 issue and on their website titled "As the American Dream dies, we must rethink our suburbs, homes, and communities." It is part of a series of articles that mark the AIA National Convention in Orlando that took place at the end of April.

Americans define themselves through work; it builds character, or so we believe. The American Dream is premised on individual achievement, with the promise that our labor will be rewarded and measured by the things we collect and consume. For many, the sine qua non of the dream, our greatest collectible, is the single-family house. Of all our products, it is the one we most rely upon to represent our aspirations and achievements.

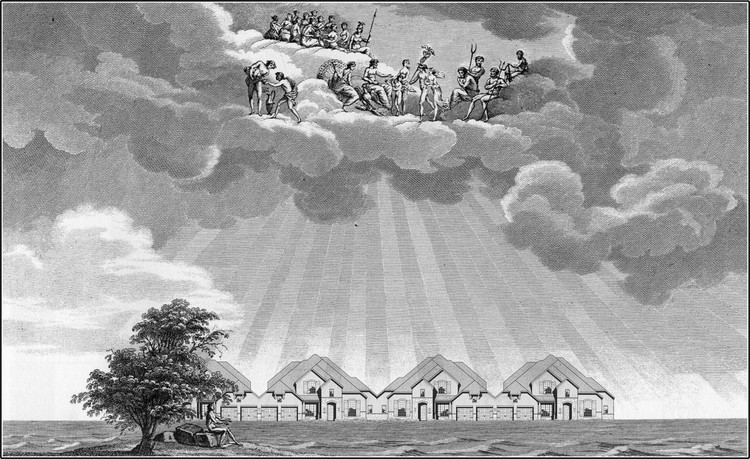

Throughout the history of our republic, the idea—promoted from the beginning by the likes of Thomas Jefferson, heir to Palladio and father of the American suburban ideal—of living in a freestanding house in the middle of one’s own personal Eden has been the dream of generation after generation of Americans. So while it was possible for Le Corbusier to say, in Paris near the beginning of the last century, that “A house is a machine for living,” from our perspective, on this side of the Atlantic and on this side of the 20th century, it would be better to append that famous maxim: “A house is a machine for living the American Dream.” At this point in history, this statement seems entirely self-evident but still we are reminded by our leaders to get our piece of the dream. In promoting his vision of an “ownership society” in a speech at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church in Atlanta in 2002, President George W. Bush said, “I do believe in the American Dream… Owning a home is a part of that dream; it just is. Right here in America, if you own your own home, you’re realizing the American Dream.” And during the early years of the new century, the economy soared as millions of wood-framed dreams sprang up across the country, enabled by an elaborate new financial calculus cooked up by Wall Street.

But then the magic formulas—which scripted the construction and consumption of ever-larger houses in ever increasing numbers by bundling our dreams together into tradeable units—began to fail. The dream quickly became a nightmare. As the legitimating environmental, economic, and socio-political narratives that for so long sustained the endless reproduction of suburbia began to collapse, it became clear that the suburban house, rather than the manifesting of our achievements, masked our delusions. According to the historian John Archer, “the romanticized isolation of the individual (or nuclear family unit) in a manufactured Arcadian preserve is an increasingly untenable fiction.”

The myth that we all stand alone, propelled by our own initiative and hard work is part of that fiction. Suburbs, and the detached single-family houses of which they are comprised, reinforce it. They work to isolate and separate us, to dislocate us as individuals, detached from any larger heterogeneous collective body. The common cul-de-sac is, both literally and symbolically, the end of the road, a terminus in a system. Safely sequestered within its four (or eight, or sixteen, or thirty-two) walls, we stand apart from the crowd, reaching out through an array of devices to make contact with those who are, more or less, just like us. Space becomes less a medium in which we mix and more a barrier that insulates us from those unlike ourselves. And as houses balloon in size, this sense of disconnection is amplified within the walls of the house itself, with each inhabitant withdrawing to ever more far-flung and insular domestic realms.

The social and political consequences of this withdrawal are increasingly obvious in the deterioration of a civil society and the erosion of civil discourse. The further we live from each other, the less we are capable of seeing each other as people with shared dreams and struggles and the more likely we are to see an other, unlike us, whom we fear and demonize. The evidence of this is clear in the last election, in which President Donald Trump’s campaign of xenophobia claimed the most votes, according to the Washington Post, in our suburbs, small cities, and rural areas. As our houses spread out—as the distance between us increases—we vote more myopically to protect our own perceived interests (and the interests of those we see as like us) at the expense of what is arguably the greater collective good.

But is the detached house, with its resulting social detachment, a prerequisite of the American Dream? Is it possible to imagine other futures for the dream and, consequently, other futures for dwelling? What would happen if personal happiness were no longer so closely tied to economic success derived from the fruits of one’s labor? These are questions we would do well to consider. Jobs are disappearing. And while presently most of us still need—and may even want—to sell our labor, it is becoming clearer that with each passing day there will only be fewer buyers. Our relationship to work, and therefore to the American Dream, and therefore to our manner of dwelling, and therefore to politics, is changing.

According to the network theorist Geert Lovink and the political activist Franco Berardi, the capitalist promise of “full employment turned out to be a dystopia: there is simply not enough work for everyone... Zero work is the tendency, and we should get prepared for it, which is not so bad if social expectations change, and if we accept the prospect that we’ll work less and we’ll have time to think about life, art, education, pleasure, love, and what have you rather than solely about profit and growth.” Our current world is built on a foundation of profit and growth. Our urbanism—and the infrastructure and architecture with which it is constructed, including the tens of millions of homes spread thin across the landscape—is the result of a centuries-old economic system. And that system has consistently sought to segregate sites of labor and production from sites of dwelling. The single-family house in a suburban bedroom community along a congested commuter route is the product of a capitalist system in which we head out each day to sell our labor in an indifferent market, returning as night falls to replenish our energies and reclaim our identity.

As the market for labor decreases in an increasingly automated world, we need to begin thinking about the consequences and benefits of a future without work, or, more accurately, with far less wage-earning work. Even now we can see that a shift is occurring. The recent collapse of the distinction between places of work and living is both a symptom of the underlying economic and technological transformations that are reshaping work as we know it and a sign that points toward other ways of dwelling. Out of necessity, and, in many cases, desire, people are beginning to experiment with other ways of living, coming together to form new (or new again) types of shared live-work households. And as the tendency toward zero work increases, we will all need to rethink the way we live. Because if we take the classical definition of work out of the equation, the whole structure of our cities, as well as our manner of living, makes a lot less sense.

Already, this probability is leading economists, technologists, and political scientists—but sadly few politicians on either the left or the right—to speculate on the structure of society in the future. A key question is how people will sustain themselves without jobs. There are renewed calls for a universal basic income by tech leaders like Elon Musk (or a universal basic dividend suggested by Greek economist and politician Yanis Varoufakis); Bill Gates has even suggested that we have an income tax on robots. In any case, a new economic model—which will, necessarily, be accompanied by a new political order—in which we are freed from the obligation to sell our labor in order to survive will require that we consider other conceptions of human productivity, other forms of human association, and of course other ways of living.

In such a future, the American Dream, as it is currently defined, would have no utility. But how would we organize our lives in a world where we work less? What would we do? How would we live? In his essay “Fuck Work,” the historian James Livingston points toward an answer when he asks, “How would human nature change as the aristocratic privilege of leisure becomes the birthright of all?” As architects, seeking a way forward, we might ask a different version of Livingston’s question: How would human habitats change, as the privilege of leisure becomes the birthright of all?

Liberated from the idea that our dwellings must be understood as freestanding castles, as isolated retreats from society through which we represent our individualism and secure our market share, we could instead conceive of assemblages of dwellings that collectively define a domain of mutual cooperation, interaction and civil discourse. We have counter-histories of dwelling that offer us guidance in thinking about other possible domestic orders. In 1886, Jean-Baptiste Godin, the French industrialist who built the Social Palace at Guise, wrote that when “constructed with a view to unity of purpose and interests, the homes, like the people, approach each other, stand solidly together, and form a vast pile in which all the resources of the builder’s art contribute to best answer the needs of families and individuals.” And following this, we might allow ourselves to imagine—as a way of shaking off the dust of the 20th century—living in what the social reformer Robert Owen described as a “magnificent palace, containing within itself the advantages of a metropolis, a university, and a country residence, without any of their disadvantages, …placing within the reach of its inhabitants… arrangements far superior to any now known … [nor] yet possessed by the most favored individuals in any age or country.”

Of course, the American Dream can’t be transformed overnight. There are aspects of it that are deeply embedded in our collective consciousness. At its core, the dream is about security, comfort, and familiarity, as much as it is about aspiration, accomplishment, and status. Any new ideas about the way we live, if they are to dislodge us from our long-habituated connection to the single-family detached house, must be accompanied by new architectural models and delivered through compelling new narratives that situate the needs and desires currently manifest in the house within new patterns that make collective life more desirable.

This may seem to be yet another call for a utopia, and therefore criticized as being divorced from the pressing concerns of the real world. It is not. For as Lewis Mumford said, “the prospects of architecture are not divorced from the prospects of the community. If man is created, as the legends say, in the image of the gods, his buildings are done in the image of his own mind and institutions.” The real world is changing rapidly all around us; meanwhile we cling to increasingly outmoded dreams. In the future, if we hope not only to survive but also to thrive, we’ll need to change our minds and rethink our institutions. We’ll have to prioritize community as much as we currently prioritize individuality. We’ll have to decide to live together. We’ll need new dreams.

Keith Krumwiede is the author of "Atlas of Another America: An Architectural Fiction" (Park Books, 2017).