In this new collaboration, originally titled "Architecture for the system and systems for architecture," Spanish architect and cofounder of the blog MetaSpace, Manuel Saga, reflects on the experience of developing (and taking on) a game where architecture plays a key role for the designer, and for the player. The case studies? No less than four major titles of our times: Starcraft, Age of Empires, Diablo and Dungeon of the Endless.

On MetaSpace we have introduced a general overview of the challenges that video game designers face when creating buildings, cities and even maps. This time we will go one step further: what happens when a game doesn’t offer a narrative or a fixed, open map, but rather an architectural system that the player can take control of? How does a design team respond to something like that?

Let's take a look.

Architecture for the System

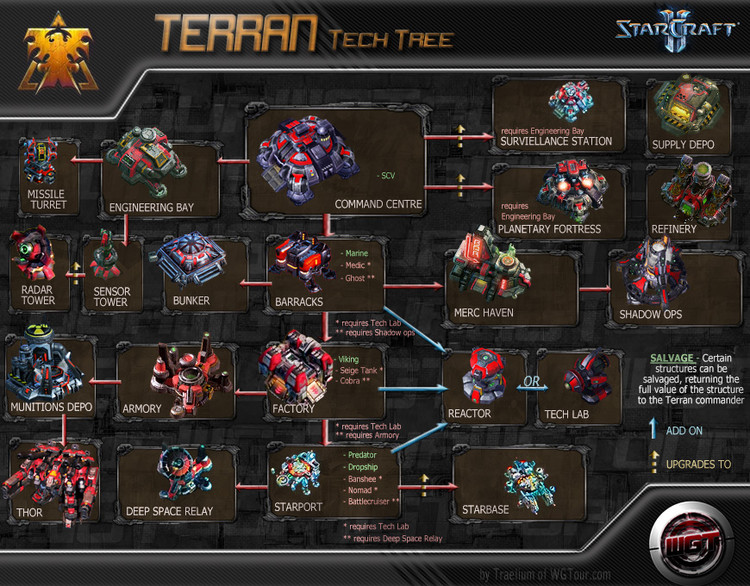

A classic example of this type of game is Starcraft: a strategy game in real time, where you have to manage a military base in order to build an army powerful enough to overcome your opponent. In games of this genre, you usually start the game with just a command center and some workers, who need to collect the necessary resources to expand your facilities, generate the appropriate units and tactically respond to various situations that the enemy poses. There is always an ideal strategy when facing certain situations, the challenge is knowing how to quickly adapt your style of play.

Ultimately, it consists of a very well integrated system of resources, buildings and units. Under the aesthetic surface is a network of attributes, damage points and movement speeds. Like a kind of complex, super-chess, the real core of the game is in its rules, which determine its gameplay and complexity. The longer you play, the better you understand the system and can anticipate your opponent's actions. The winner will be the one who knows the system the best and adapts to it.

All this is fine, but so many numbers and rules would be boring without context. Building a site for gathered materials doesn’t sound that same as teleporting a colossal pyramid from an alien planet, right? Here lies the challenge of the designer. They must be able to translate the system rules into a set of easily recognizable designs, identifiable by their role within the game and adaptable to any situation that may arise. This applies to the design of characters and units, but also to buildings and cities, to the architecture.

There are the large main buildings that stand above the rest, and others that are medium-sized and small outposts. The design should suit the style of the game. In Starcraft, for example, the Terrans are humans of the future with super-tech buildings that can fly. Meanwhile, the Zergs are an alien race based on organic matter, including an infrastructure of living buildings. In both cases, the constructions of both races should be easily recognizable by the players, in any given configuration. That's the challenge.

This same problem applies to games in completely different settings, like the well-known Age of Empires. In this game, the logic is exactly the same: build a base and beat your opponent, but instead of controlling aliens from the future you’re Joan of Arc, William Wallace or El Cid. You manage resources, create structures and train your soldiers in a manner analogous to Starcraft -- but the interaction between these elements is different, as is their contextualization.

Age of Empires stands out with the careful design of its buildings, particularly that of its castles. The game has its own encyclopedia, where you can see the historical role that buildings had or the royal castles that the designs were based on. Its scope has been such that even now, years later, projects have been developed to improve its graphic models, like the Architecture Renovation Mod website, which makes various changes to the architecture to make it more dense, with more detail and realism, even though it’s more inconvenient to play.

Architectural Systems

On the other hand, there are games that pose the opposite challenge: rather than creating a system that the player manages, they create a system with spaces that can be reorganized in each game, adjusting and changing for different levels. For example, in the Diablo saga you have to move through a dungeon that’s different every time you enter it, creating a permanent and highly addictive challenge.

However, as in any system, these games have permanent rules governing their spaces. Although they may change, they need to maintain a basic consistency. For example, if the player is supposed to go through a city of narrow corridors, the "architectural pieces" of the system must comply with this rule. If you want the player lost in a vast desert with few clues for orientation, the rules need to be different.

Another good example of this approach is Dungeon of the Endless, a title which, as its name suggests, makes you navigate a dungeon that is seemingly endless. To accomplish that effect there is a predetermined system of rooms and corridors that are arranged differently for each level. Some rooms have "outlets" where you can build machines that help you move, others offer no help or even have traps, monsters, or poisonous clouds. In this sense, the challenge is very interesting, because you never know what you’ll find. It’s completely up to chance. A game can be simple or present challenge after challenge, making you "suffer," but giving you a great feeling of accomplishment when you "beat the system."

This example has three elements that are particularly interesting for architects. One is its interface, which is like a kind of freeform plan where the walls appear broken up into sections. The second is its map, designed to manage the various rooms that we mentioned. The third and most important is the door, since entering a new room can change the game completely. The title sequence utilizes this element, showing heavy doors that slowly open with a creaking noise, causing an unbearable curiosity especially if you’re doing poorly in the game. Will you finally find that treasure and win? Or will an interdimensional beast appear, making you unleash a string of expletives?

If you take a step back, you can see the influence that role-playing maps -- used since the 70s -- had in Dungeon of the Endless, where the narrator arranges the rooms differently in each iteration. The davesmapper tool is a good example of this, generating thousands of random maps for role-playing games.

Grow Between Systems

Designing a system of random spaces and contextualizing them for coherence is not original to video games. From the battlefield of the chessboard, to Chutes and Ladders or Monopoly, in our childhood (and well past our childhood) we had fun placing houses and hotels in strategic locations.

In fact, architecture as a system is a research topic starting in the Modern Movement, seeking to provide lots of solutions from a limited number of elements. Many of these projects were presented as a building game. We all have a vague idea of how the master bedroom (the Dragon’s den), or Dad's office (the throne room) or the basement (the bloody catacombs) should be. If we start from a systemic approach to architecture, the rules that we establish between those elements are what will give consistency to the game.

Video games teach us that, beyond getting the game to work, in order for it to be fun and interesting, you also need to establish a character that is innovative and very much its own. You need to let your imagination run wild.