Looming over the small Bavarian town of Hohenschwangau are the turrets and towers of one of the world’s most famous “fairytale” castles. Schloß Neuschwanstein, or “New Swan Stone Castle,” was the fantastical creation of King Ludwig II – a monarch who dreamed of creating for himself an ideal medieval palace, nestled in the Alps. Though designed to represent a 13th-century Romanesque castle[1], Neuschwanstein was a thoroughly 19th-century project, constructed using industrial methods and filled with modern comforts and conveniences; indeed, without the technological advancements of the time, Ludwig could never have escaped into his medieval fantasy.[2]

The seeds of Ludwig’s dream were sown during his childhood. The young Prince spent his summers in the nearby castle of Hohenschwangau, itself a reconstruction built by his father Maximilian II in the 1830s. Built over medieval ruins discovered by Maximilian during a hunting trip, Hohenschwangau was one of the first Romantic revival castles built in what would eventually become Germany; its combination of English Gothic styling with contemporary conveniences would serve as a formative influence for Ludwig’s own castle just across the valley.[3]

Ludwig was also enamored by mythology and folklore, especially as portrayed through opera. Within a year of taking the Bavarian throne in 1864, the King summoned and became a patron to composer Richard Wagner. Under Ludwig’s reign, music flourished in Bavaria’s capital of Munich.[4] As the new King faced mounting criticism and opposition in Munich, he began to withdraw from the city into the mountains (to Hohenschwangau) and into the legends illustrated so vividly by Wagner’s operas. There, in the fantasies of the past, Ludwig could escape the strife that was his present.[5]

The final straw came in 1866, when a military defeat against Prussia led to the restriction of Ludwig’s powers as king. No longer a sovereign ruler, Ludwig compensated by building himself a series of palaces in which, from 1867 onwards, he could play autocratic monarch. Like his father, he chose the site of two ruined castles as the base for his own new palace. Unlike his father, however, he was dedicated to creating a castle that hewed more closely to the style of its forebears than Hohenschwangau had. Inspired by Wagner, Hohenschwangau, and the castles of medieval Germany, Ludwig commissioned scenic painter Christian Jank and architect Eduard Riedel to begin construction of “New Hohenschwangau” – what would eventually come to be known as Neuschwanstein.[6]

Though Riedel initially planned to build up Neuschwanstein from the ruins on the site, it soon became clear that Ludwig’s vision would necessitate demolishing them to clear the way for something of a grander scale. The alpine ridge proved to be an incredibly challenging construction site; a road had to be built to ascend 200 meters to the summit of the mountain, which had to be laboriously flattened into two adjacent plateaus in order to serve as safe foundations for the castle. Subsequent construction made use of one of Germany’s first large steam-powered cranes, which became a highly visible anachronism next to the medieval castle that took form beside it. Industrial techniques would continue to serve the architects and builders as construction proceeded; innovation the only way for them to keep up with Ludwig’s impatient deadlines.[7]

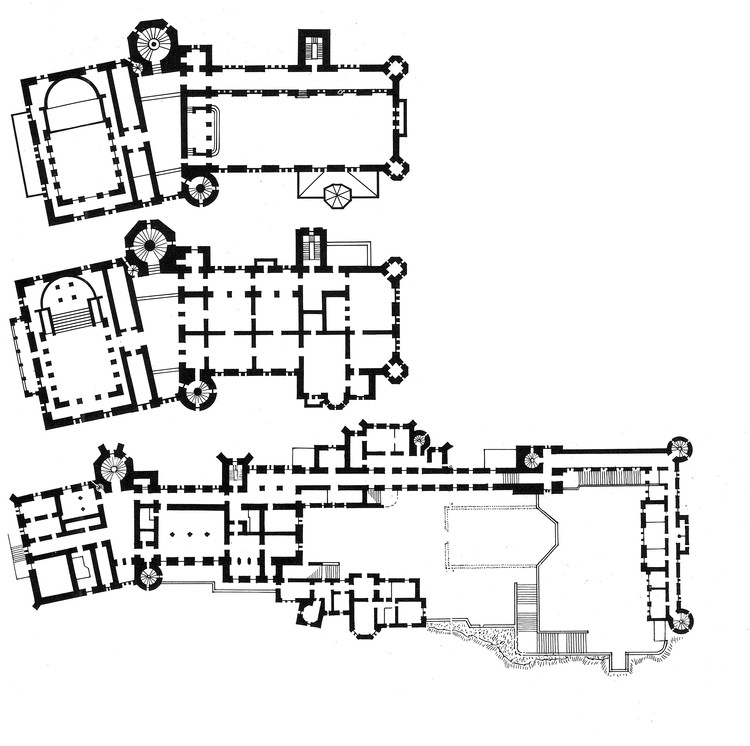

Neuschwanstein, as envisioned by Ludwig and illustrated by Jank, was an idealized Gothic castle. Ludwig’s visit to a contemporary reconstruction of the Wartburg Palace, however, saw the concept shift to a larger Romanesque castle with multiple structures leading to a five-story royal residential building, or palas.[8] When the first foundation stones were laid in September of 1869, Ludwig fully expected to be living in his completed castle within three years. However, it would be four years before he could move into the gatehouse, which was, at that point, the only space ready for habitation.[9] The palas was topped out another seven years later in 1880; Ludwig finally moved into his intended apartments in 1884.[10]

Once the gatehouse and palas were ‘topped off,’ work could proceed on the accessory structures and the lavish interior of the palas itself. The complex, as designed, featured the following spatial elements: a gatehouse, two courtyards, the palas, a Keep with an ornate chapel, a Knights’ House, a Ladies’ House (or “bower”), and a square tower. The structure was to be composed primarily of brick, sitting atop a cement foundation and clad in limestone.[11] The bower and square tower would not be completed until after the King’s death in 1886, and even then only in a simplified form; the 90-meter tall Keep, which would have featured a Gothic chapel at its base to form the heart of the castle, was never realised.[12]

While much of the interior of the palas was never finished, the few rooms that were completed form a vivid image of Ludwig’s ultimate dream for Neuschwanstein. The King’s apartments on the third floor feature an ornately decorated Gothic bedroom, an artificial grotto inspired by a Wagnerian opera, and a winter garden whose panoramic view of the Alps surrounding the castle are sealed in by what were, at three meters tall, the largest window panes ever made at the time.[13]

These windows, which would have been impossible to craft during the medieval period, were not the only contemporary features of the palas: the entire building was equipped with central heating and running water, with the King’s lavatory even featuring an automatic flushing mechanism. An electric bell system allowed Ludwig to summon servants from elsewhere in the castle, while a pair of lifts allowed them to reach him without climbing any stairs. Perhaps the most egregious anachronism, however, was the pair of telephones fitted into the third and fourth floors.[14]

While industrial technologies were primarily employed for ease of construction or as a concession to human comfort, there was one case in which it was necessary for the very structure of the castle. Rising from the third into the fourth floor, the lavishly gilded Byzantine throne room was to be the chief showcase of Ludwig’s divine right as King of Bavaria; every detail, from its profusion of Christian mosaics to its crown-shaped chandelier, was meant to proclaim his role as the intermediary between heaven and Earth.[15]

Although it is not immediately apparent from within the space, the throne room is actually supported by a framework of steel members. Girders form a structural lattice above, supporting the ceiling and the arched apse above the dais, and even the dais itself rests upon iron supports.[16] It is almost poetic that the throne—the element that would have most directly represented Ludwig’s idealized medieval kingship—would have secretly been supported by features of a period in time he had come to despise: his own. The throne room carries an added symbolism, however, in that it was never fitted with the item that would have given it its purpose: the throne itself.[17]

Ludwig’s increasingly tenuous financial and mental state led his government to depose him on the grounds of insanity on June 10, 1886. He was removed from his home at Neuschwanstein two days later to a mental hospital at Berg Castle. The following evening, he and his psychiatrist were both found dead at the shore of Lake Starnberg.[18]

Seven weeks later, the Bavarian government opened Neuschwanstein to the public, turning the late King’s private recluse into a tourist destination which is today visited by 1.4 million people every year.[19] Neuschwanstein has become world-renowned as an icon of the ideal Romantic castle, both in itself and as the main inspiration for Disneyland’s Sleeping Beauty Castle.[20] While Ludwig II was ultimately unable to escape his troubles, his greatest fantasy—his beloved Neuschwanstein—endures.

References

[1] "Neuschwanstein Castle." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.schloesser.bayern.de/englisch/palace/objects/neuschw.htm

[2] "Interior and modern technology." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.neuschwanstein.de/englisch/palace/interior.htm

[3] Knapp, Gottfried. Neuschwanstein. London: Edition Axel Menges, 1999. p7.

[4] "King Ludwig II of Bavaria." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.neuschwanstein.de/englisch/ludwig/biography.htm

[5] Gottfried, p9.

[6] "Idea and History." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.neuschwanstein.de/englisch/idea/index.htm

[7] Gottfried, p11.

[8] "Neuschwanstein Castle - an example of Historicism." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.neuschwanstein.de/englisch/idea/histor.htm

[9] Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. "Neuschwanstein Castle", accessed March 29, 2016, http://www.britannica.com/topic/Neuschwanstein-Castle.

[10] “Idea and History.”

[11] "Building History." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.neuschwanstein.de/englisch/palace/history.htm

[12] Desing, Julius. The Royal Castle of Neuschwanstein. Lechbruck: Kienberged GmbH, 1998. p9.

[13] Gottfried, p15-17.

[14] “Interior and modern technology.”

[15] Desing, p16-21.

[16] Gottfried, p15.

[17] Desing, p16.

[18] Cowan, Henry J., and Trevor Howells. A Guide to the World's Greatest Buildings: Masterpieces of Architecture & Engineering. San Francisco: Fog City Press, 2000. p79.

[19] "Neuschwanstein Today." Bavarian Palace Department. Accessed March 26, 2016. http://www.neuschwanstein.de/englisch/palace/index.htm

[20] Cowan and Howells, p79.

- Year: 1886