This article was originally published on September 8,2014. To read the stories behind other celebrated architecture projects, visit our AD Classics section.

The next time you catch the scent of a Glade air freshener or evade pesky mosquitoes thanks to Off!, think of Frank Lloyd Wright. His 1950 building for the SC Johnson Research Tower at their headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin, was home to the invention of many of their landmark products.

A corporate commitment to innovation combined with Wright’s penchant for visionary design, yielded a pioneering yet challenged structure. An expansion of the company headquarters adjacent to the Wright-designed Administration Building from a decade earlier, the tower design expanded on the architect's visions for modern workspace and biomimetic structural systems. Floor slabs cantilever from a reinforced concrete “taproot” core, and bands of brick and crystalline glass tubes enclose laboratory spaces. Reverently maintained yet mostly unused by the SC Johnson company today, the tower can be considered either form pursued at the expense of function or a daring architectural accomplishment.

Ten years after the completion of the SC Johnson Administration building, construction began on the Research and Development Tower. The company required laboratories for their emerging research and development department. Despite trials during construction and maintenance of the Administration Building, third generation leader Herbert Fisk Johnson and Wright formed a close relationship, facilitating unprecedented design freedom for the architect. Johnson anticipated a building “in which beauty and function are so spectacularly combined, [that it] will prove an inspiration to the men and women who work in it.”

For Wright, the Johnson Buildings represent a break from the Prairie style, infusing aesthetics from streamline modern into his materially rich and light driven vocabulary.

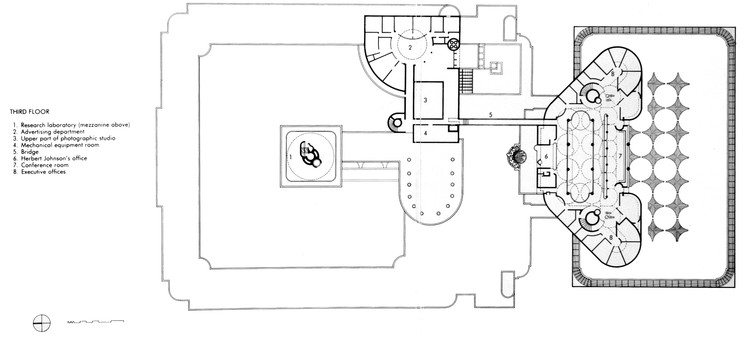

Connected to the Administration Building by a bridge, the Research Tower rises 153 feet above ground and bores 54 feet underground. The headquarters are located in Racine amidst wax and paint factories, movie houses, stores and homes. Because the urban site lacks the natural context Wright so valued, visual and physical connections to the context are minimal. The main entry for the tower is located near the carport, under the building. After taking a cylindrical elevator to the second level, a slender bridge sheathed in an arch of glass tubes leads the way across to laboratory spaces.

The compact, tightly-coiled vertical mass rises in contradistinction to the expansive horizontality of the administration building. Unlike the cavernous Great Workroom, the minimal floor plates and low floor-to-floor distance in the tower create a compressed space. The administration building, with its impenetrable brick, sequesters workers within a grand hypostyle hall. The ratio of solid to translucent inverts as the largely blank brick faces of the administration building give way to large crystalline bands in the tower.

Yet both buildings are cut off from the outside world and articulate the façade as independent wrappers of the structure. Although the predominantly glass walls admit ample light and serve as a glowing beacon at night, the tube construction distorts vision from inside and out. For building occupants, the exterior world amounts to indistinguishable shifting colors and masses.

By leaving the first floor of the tower eroded, Wright reveals the singularity of the tower’s structural support. Second and third floor offices as well as a roof terrace hover on dendriform columns.

A compact trunk-like core of conjoined tubes provides all building services to support lab spaces: restrooms, circulation, supply and return air, electricity, water, illuminating gas, compressed air, carbon dioxide or nitrogen, steam and direct and alternating electric current. The tower form minimized the length of utility distribution distances in comparison to a conventional low building.

In section, each slab attenuates towards the façade, reflecting the diminishing shear and moment forces of the cantilever while also echoing the shape of the dendriform column capitals. The building alternates between smaller circular floors and square floors with filleted edges that extend all the way to the enclosure.

The residual space becomes double height volume, connecting two floors. The slab edge turns up to form a brick clad reinforced concrete knee wall. These 4 feet, 11 ½ inch tall solid walls coordinate with the casework that rings the perimeter. Wright worked closely with scientists on the installation of furnishings within labs.

Because every other floor is a mezzanine set back from the exterior wall, Pyrex tubes span the height of two floors between brick spandrels. The resulting oversized scale further abstracts the reading from the exterior. When lighting conditions reveal the silhouette of the intermediate floor plate, the tower appears as a crystalline mechanic apparatus. The Pyrex tubes are held to aluminum stanchions with wire, and an inner plate of glass lines the exterior. Leaks caused by the failure of the neoprene gaskets between tubes were a persistent issue until a new sealant was developed.

The Research Tower received wide coverage and positive reviews both during design and after completion. Architecture as well as general interest and business publications featured the building, as did two MOMA exhibits during the 1950s.

However, building occupants gave a more mixed review. The vertical nature of the tower all but precluded casual interaction, and a slow elevator discouraged stopping in on all but the most immediate colleagues. In addition, the extremely low ceiling height adjacent to the core conflicted with equipment use. As the number of employees and heat producing equipment increased over the years, the building became difficult to heat and cool. The glass tube walls leaked but were “capable of creating a gorgeous visual effect.”

In 1982, SC Johnson opened another facility to house its expanding research department. The tower was all but abandoned due to safety concerns – evacuating in the event of an emergency would be difficult with only one tiny staircase. Yet the SC Johnson company has painstakingly maintained Wright’s vision and details. In 2013 the tower underwent renovations, replacing over 21,000 bricks and 5,800 Pyrex tubes. Three levels of the fifteen are currently in use as office and exhibit space. Because upgrades to meet building code would compromise Wright's design, the company has no plans to convert remaining floors into usable office space. Starting in May 2014, the tower was opened again to public tours.

The Research Tower, along with the Administration Building, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

For more information or to read about the nearby schedule a visit to the tower.

Sources

Lipman, Johnathan. Intro by Kenneth Frampton. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Johnson Wax buildings. New York: Rizzoli: 1986.

Siry, Josepth. “Frank Lloyd Wright's innovative approach to environmental control in his buildings for the S.C. Johnson Company.” Construction history: journal of the Construction History Group 28, no. 1 (2013):141-164

-

Architects: Frank Lloyd Wright

- Year: 1950

-

Photographs:Ezra Stoller/Esto, SC Johnson

Bernstein, Fred A. “A Masterpiece, With Shortcomings.” Architectural Record. April 21, 2014. Accessed at http://archrecord.construction.com/news/2014/04/140421-A-Masterpiece-With-Problems.asp